Interviews: Professor David Farber (1)

(Part 1) - How one Child became the "Grandfather of the Internet" - A Seed Planted in the 1940s

Who set the stage for the information age we are living in now? This is the tale of a man who is sometimes called the "Grandfather of the Internet"--a critical player in the development of the Information Age as we know it today.

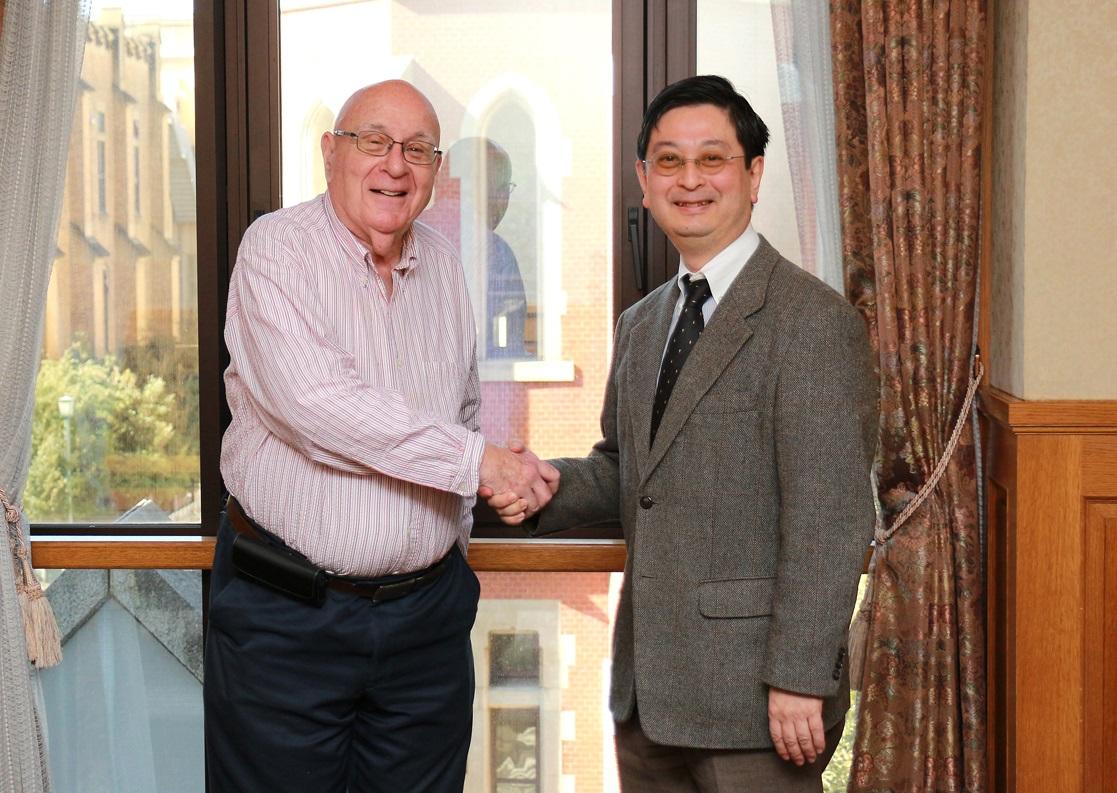

This is the story of David J. Farber, who arrived in Japan in April 2018 as the Distinguished Professor and Co-Director of the newly-established Cyber Civilization Research Center (CCRC) at Keio University, to continue his adventure in the exploration of the future of the Internet.

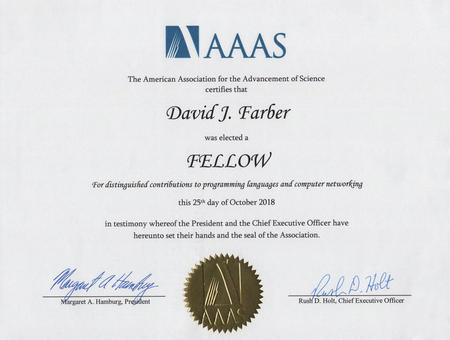

To celebrate his election in late 2018 as a AAAS Fellow of the Council of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, this story explores and uncovers Farber's incredible journey--the serendipity of his circumstances, coming of age in the early stage of cyber civilization.

For this article, Professor Jiro Kokuryo from Keio University sat down with Farber to listen to his life story.

*Jiro Kokuryo: Vice-President / Professor, Faculty of Policy management

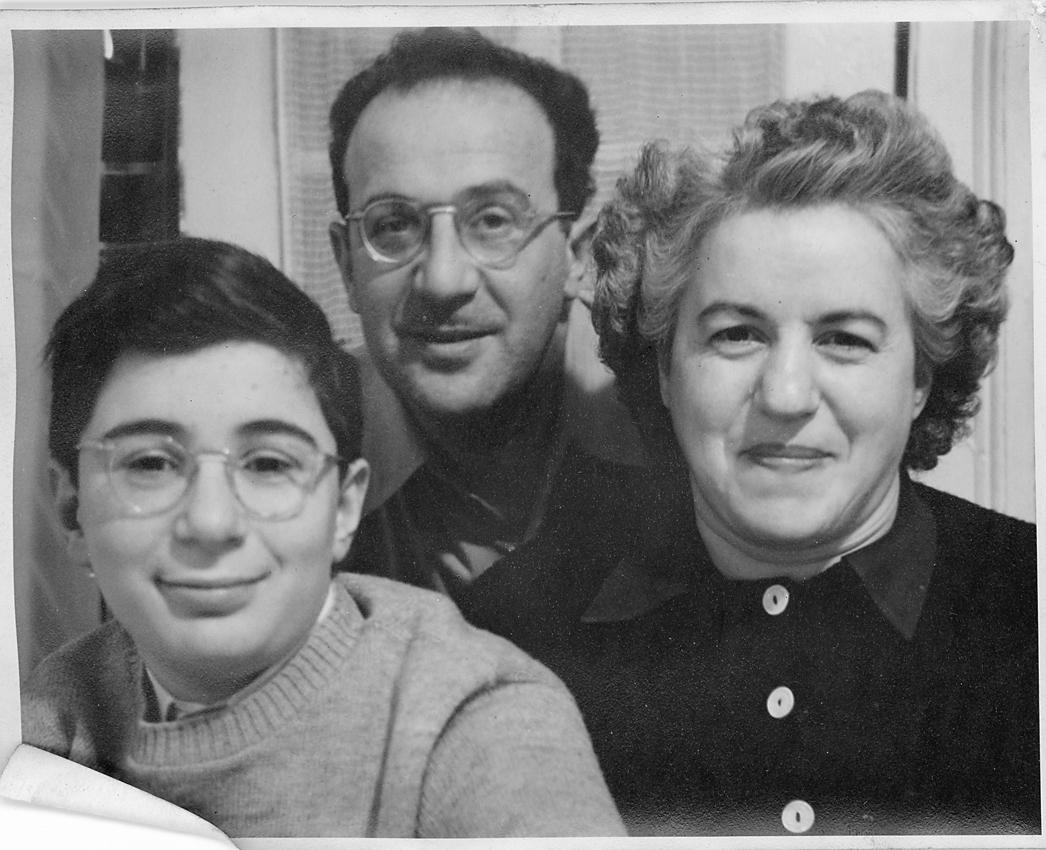

Growing up in the Early 40's

"I was born in New Jersey, 1934." Farber starts to reminisce on his childhood. "My father was a foreman in a seed and spice importing firm in New York City, where he worked for the rest of his life. What I remembered as a child in the early 40s is that we lived at the back of my grandfather's store, and that in winter we had a kerosene stove, and an icebox hanging from a window to keep stuff cold. Comfortable place, not upscale. My father never made much money."

Farber still vividly remembers two things from these early days: the time he had a very bad case of pneumonia, and the exact day in 1942, when he heard on the radio about Pearl Harbor.

"Those days are very vague," Farber reflects. "I was very young and remembered only a few snippets of it."

Farber's memory jumps to 1946 to downtown New York where people were selling all sorts of wares. "I was 12 years old. This was after the war was over, and downtown New York used to have an area where they sold surplus electronics stuff from the military. I liked to go roaming around the area--back then, it was not unreasonable for a 12 or 13-year-old boy to go travel a little bit on his own to NYC."

Farber says he didn't find anything very interesting, "but it was still my introduction to electronics."

Other things that got him interested in electronics were the early television his family had and the "Heathkits" that were available at the time. "It was a kit that you could use to build your own radio. And a good thing about it is that it had a manual that told us why it worked. And they were easy to build, and affordable." He says those kits vanished not long after that time. "Boy, I miss seeing that now. There is no equivalent thing that I can find."

This Heathkit was, for the young Farber and for the people who were interested in radio and technology in those days, a big introduction to the world of modern technology.

His memory rolls a little forward to his days at high school. He started high school in Jersey City, but moved to another school in Lodi, a nearby borough.

"Back then, I wanted to be a cosmologist." He was inspired by books on cosmology and the Hayden Planetarium, "But in the end, I gave up, partly because I was convinced by a school counselor saying it was not a good idea for earning a living. But to this day, astronomy and cosmology remain an area of interest for me."

In high school, he excelled at mathematics. He used Boolean algebra for a literature term paper assignment, by analyzing an author with Boolean logics. As Boolean algebra is one of the first steps in learning computing architecture, this episode shows how he was unwittingly already getting into the field of computing.

As Farber neared graduation and started to think about college, "I had to worry about tuition, because my family had no way to afford college." He explains how he started a weekend job at a grocery store which he did during the last two years of high school.

"I earned enough for one year in college, although once I was admitted to college, my aunt offered to help with my tuition because I was the first kid in our family to get into college."

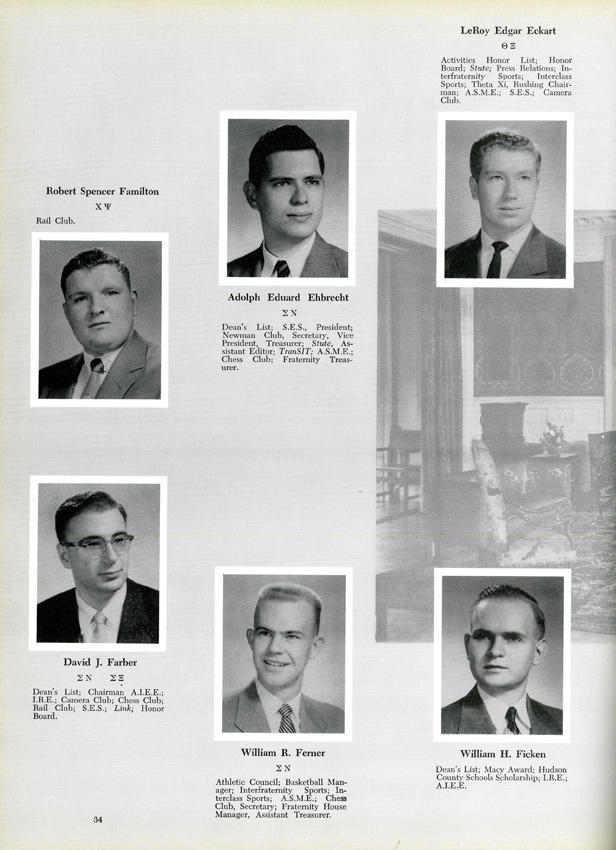

He eventually attended Stevens Institute of Technology. "I don't really remember completely why I chose it," he says, "but I was probably considering the location and tuition, as well as the degree Stevens gave-- 'mechanical engineer.' This general engineering program seemed attractive to me because at that point I was not sure what I wanted to do. Engineering looked interesting because it was a lot of things, and it was math-based."

It turned out that Stevens was an excellent general engineering school.

"You've got a little bit of everything, including how to weld, how to do gears, cast the gears, machine the gears, the whole deal. And I found that all really interesting, even though I didn't get near it in my future career. I understood how things are built, and we had to actually build these things." Academically, he performed well. "As I moved [to a dormitory] on campus, I also learned a lot from fraternity. Living with a bunch of people had a major impact on me socially."

Farber moves on to his memories from his time at the lab of the US Navy Department in Washington, D.C., where he went for a summer job in his junior year.

"I got the job with a guy named Detrich Wally, who had built the world's first transistor analog computer," says Farber. "It was in the days when air-conditioners were scarce," he says. "Let alone my fraternity house in Washington, even the navy building didn't have AC, except two rooms: the cryptographic room and the lab, to protect the transistor from burning up. So, I spent a lot of time in the lab, talking with Detrich and others."

"Analog computers are strange things. You needed to be very sensitive to electrical ground levels." He recalls the first test-run they had gone through. "We got this beautiful curve, except that it was not what we should have gotten. Then we saw a little squiggle up there; that was what we wanted, the rest was the ground noise."

Farber says he spent a huge amount of time learning about analog computers. "And that got me interested in the possibilities of computing. Although it was an analog computer with limited capacity, it was still a valuable thing."

When was Farber's introduction to digital computing? It happened one year after his encounter with analog computers, when he and his classmates were making a prototype for a senior thesis.

"We talked to a chemistry professor, who had an idea of an automatic chemical analyzer.... Our senior thesis was to build it, make it work. So, we tried making it. And much to my astonishment, we built a relay-controlled computer with an input of a huge punch card. It actually worked and was used for years after that," says Farber.

Farber thought it was time to make a decision. After touring around he decided to go to graduate school. His grades were good enough, so he applied to various schools.

"And the serendipity of that moment, that probably made my future." Farber, now 84 years old, looks back fondly to that particular day when, as a 22-year-old, his life would irrevocably change course.

Photo courtesy of David Farber(except 1st and 3rd photos)

(To be continued)

Links

(Part 2) - Beginning of the Tour around Computer Science - How a Seed was Nurtured in 1950s and 1960s

(Part 3) - Stories Behind the Computer Science Network - The Blossoming 1980s

(Part 4) - Looking Forward - The "Grandfather" Calls for a Re-design of the Internet