[Event Report] KGRI 2040PJ International Symposium "Is health distributed equally? -Global aging, Healthy aging-" (held on October 20, 2022)

2022.12.16※Click here to watch the video

On October 20, 2022, the international symposium "Is health distributed equally? Global aging, healthy aging" was held online.

The Extending Healthy Life Expectancy Project team invited Professor Katsunori Kondo, (Professor, Center for Preventive Medical Sciences, Chiba University; Head, Department of Gerontological Evaluation, Center for Gerontology and Social Science, National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology; and President, Japan Agency for Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES)) to talk about the "social health gap" in Japan, its mechanisms, and how to reduce the health gap in the society. In addition, Dr. Daniel Holman (Healthy Lifespan Institute; Department of Sociological Studies, The University of Sheffield, England) was invited as a commentator. This 1.5-hour online symposium was hosted by Professor Masako Toriya from Keio University Global Research Institute (KGRI), and as many as 90 people participated.

The symposium started with the opening remarks by Professor Masato Yasui from School of Medicine, Keio University, and the leader of the Extending Healthy Life Expectancy Project team. He described the backgrounds of establishment of Keio University Global Research Institute (KGRI) in 2016, and the Research Project Keio 2040. He also mentioned that this symposium is a part of the Extending Healthy Life Expectancy Project which aims to develop international multidisciplinary discussion on aging and healthy life expectancy.

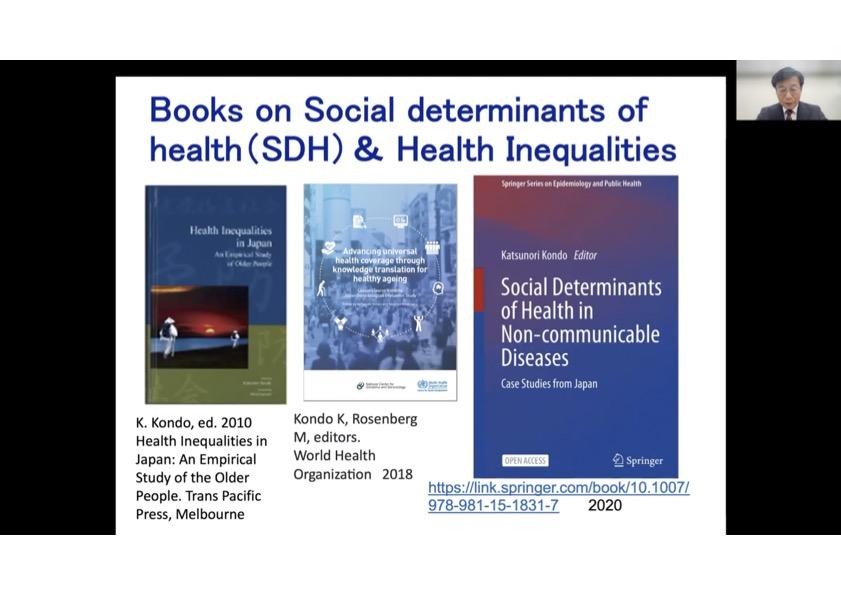

The opening remarks were followed by a presentation of Professor Kondo. In the first part of his lecture, he explained about the health gap in Japan, the processes generating the health gap, and social determinants of health based on the data from Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES), which is one of the few population-based gerontological surveys in Japan, established in 1999. One of the examples of the health gap indicated by the survey results was the relationship between income level and the prevalence of depression in elders in Japan; the lower the income the higher the prevalence of depression, with the lowest income group was five times more likely to be depressed compared to highest income group. This trend was also exhibited in the relationship between "mortality rate and incidence of functional decline" and income level; the lower income group showed higher "mortality rate and incidence of functional decline" (twice as high in females and three times as high in males) than the higher income group.

Health inequalities among prefectures in Japan were also demonstrated using data from JAGES HEART (Health Equity Assessment and Response Tool) co-developed by JAGES and WHO Kobe Center. The prevalence of depression, for example, varied between 14.9% and 34.5% depending on the prefectures. Prevalence of frailty among people who were 62-74 years old varied from 5.2% to 13.3% depending on the prefectures, and the prevalence of frailty was revealed to be correlated with the percentage of participation in sports or hobby groups in the community. A four-year longitudinal study indicated that participating in community social groups and group exercises could have a positive impact on mortality and functioning. In addition, social connection has a preventive effect on developing dementia.

Various social determinants of health are observed around the world, from "individual lifestyle factors" to "social and community networks", and "general socio-economic, cultural and environmental conditions", and they are mostly responsible for health inequalities.

The first part of his lecture was ended with the definition of social epidemiology, which is "the branch of epidemiology that studies the social distribution and social determinants of health" that is "both specific features of, and pathways by which societal conditions affect health."

Dr. Holman gave comments on the lecture of Professor Kondo. He acknowledged that the crucial message presented in his lecture was that early onset age-related functional decline and morbidity is preventable, and that the social determinants of health are key to why we see such inequalities. Dr. Holman presented the following three reflections.

- I am a firm believer in the value of the comparative policy approaches which emphasize the opportunities for countries to learn from each other and to replicate successful policies between them. In that sense, I am curious to what extent the health inequalities that have been uncovered are distinct to Japan. And where they differ, what this tells us about the configuration of social determinants in Japan versus other countries?

- How have these inequalities in Japan changed or are changing over time? Are they widening or staying the same? In the UK context the health inequalities have been widening in recent years especially the case for women. This is likely due to decades of right-wing government and lower welfare spending, austerity policies, lower investment in social and community services, coupled with increasing attention to the industries that promote unhealthy activities and products.

- In the UK, there is a stereotype that working-class, lower income people have high levels of bonding social capital, strong community networks and ties, whereas middle class people have higher level of bridging social capital, that is they are better at networking and having the right sorts of social connections to achieve success. In Japan is there a relationship between socioeconomic factors and participation in different types of activities such as sports, hobbies and social connections? How might that impact health and health inequalities?

The second part of the lecture from Professor Kondo focused on what we can do to reduce the health gap and build a healthy aging society. In the "Health Japan 21" published in 2012 by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, "reducing health inequalities" and "improving social environment" are stated as the top priorities of the direction for the next 10 years. WHO also emphasizes that individuals' functional abilities are determined not only by intrinsic capacities but also by the environments in which the individuals are living.

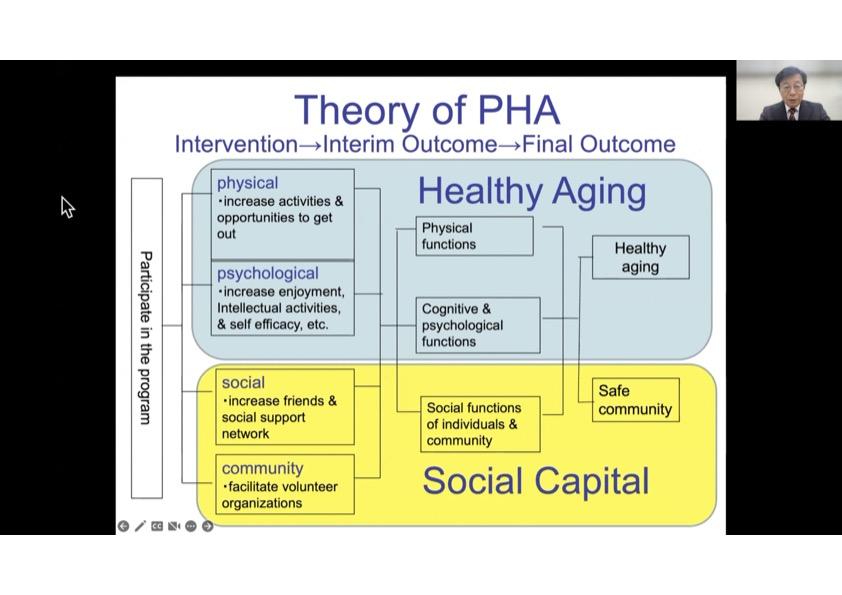

From 2007 to 2012, a community-level intervention trial was carried out in Taketoyo Town in Aichi Prefecture, Japan, to improve the social environment and to tackle inequality in social participation and active aging. This trial, whose purpose was to evaluate the Program for Healthy Aging (PHA), was organized by Taketoyo Town. The key concepts of the program were intervening in the social environment, being located in several public spaces within the town, being run by volunteers, and proving various enjoyable activities. The program resulted in positive outcomes for both individual and community levels; for example, the participants were more likely to maintain their physical and cognitive functions compared to non-participants, the feeling of happiness and number of friends increased after the participation, and the town decided to add this program to its general plan as the numbers of participants and volunteers increased yearly. In addition, it was found that this program attracted more people with lower socioeconomic backgrounds partly because people could walk to the program sites and did not have to pay much to participate.

Professor Kondo went on to present the results of the study which evaluated the impact of a national-level measure to reduce health inequalities; that is, the school lunch program in Japan. The study with approximately 20,000 elderly Japanese people revealed that those who were in high socioeconomic status in childhood tended to consume a greater amount of fruit and vegetables even in old age than those who were middle and low socioeconomic status in childhood. This trend was true for those who were over 77 years old but not for those who were between 65 to 69 years old. This is likely due to the school lunch program which was introduced to Japan after the World War II and served for those people who were between 65 to 69 years old but not those who were over 77 years old at the time of the study. This study indicated that the school lunch had a positive impact on not only increasing the weight and height of children right after the war but also a long-term effect on reducing the health gap in later life among Japanese people.

After a decade of implementation of several measures to tackle health inequalities in Japan such as Health Japan 21 in 2012 and Law on the Promotion of Policy on Child Poverty in 2013, the health gap among prefectures has significantly reduced in males but not in females.

After the lecture from Professor Kondo, Dr. Holman presented the following comments:

- I was particularly impressed by the intervention described in the lecture to tackle inequality in social participation and active aging. When I worked on a program to create type 2 diabetes peer support groups led by medical professionals, it was very interesting for me that the program created social capital among participants and the participants also reported that was a key benefit of the program even though the program was not designed to increase social participation or reduce inequalities in participation. However, one of the challenges we had was that those who took part in the program, especially the volunteer peer support facilitators to lead the groups, were typically from higher socioeconomic background. So, I am very much interested in how the Program for Healthy Aging (PHA) was able to include large numbers of lower SES participants.

- The graph which exhibited rapid increase of the height and weight of children after the WWII was quite remarkable. The interventions in later life have powerful effects, like the program Professor Kondo presented, however, childhood also sets the seeds for healthy aging in later life. It is never too late to intervene but at the same time it seems that we should put particular efforts into early life conditions because these experiences set in motion a lifetime of advantage or disadvantage, and therefore a lifetime of either healthy or unhealthy aging.

The lectures of Professor Kondo and comments from Dr. Holman were followed by discussion. Dr. Kazumi Ota from the Extending Healthy Life Expectancy Project team joined. Dr. Ota commented that, from her experience of working in a hospital as a psychologist, those who go to see professionals for physical and cognitive check-ups tend to be from middle-high to high socioeconomic status probably because they have a good access to the hospital and financial resources to do that, so that they have opportunities to receive medical attention at an early stage, and after today's lectures, she has now realized that this is one of the examples of how health inequalities can occur.

The questions from Dr. Holman to Professor Kondo were presented here.

Q1. To what extent the health inequalities are distinct to Japan? And where they differ, what this tells us about the configuration of social determinants in Japan versus other countries?

Prof. Kondo:

In Japan, there is little research on health inequalities compared to western countries. Therefore, we do not quite understand how many disparities exist in Japan. When it comes to income inequalities, Japan used to exhibit very little Gini factor, that is, wealth inequalities were comparatively small in Japan. However, now the wealth gap is prevalent in Japan. Actually, today Japan is one of the countries that show the highest Gini factor and child poverty rate amongst developed countries in the world. So, I believe that the health gap in Japan will widen.

Dr. Holman:

It seems to me that health inequalities probably most reflect social inequalities. In Japan the health gap is increasing so it is very challenging to think what we can do against the tide of widening inequality.

Q2. You have already answered this question, but in Japan, the health gap is widening or staying the same?

Prof. Kondo:

In Japan, in some aspects the health gap has been reducing but in others it has been widening, so what we need to do now is to monitor this trend and analyze it in detail.

Q3. The relationship between socioeconomic factor and social capital. Are people likely to participate in different types of sports or activities depending on the socioeconomic status? And what implications does this have for their health and well-being?

Prof. Kondo:

According to my research, some activities draw more participation from those from lower socioeconomic background than others. Activities such as sports, hobbies, and volunteers were likely to be participated by wealthier people; on the other hand, community-based activities which were found near their residences attracted more people with lower economic status. These trends were seen not only in Taketoyo Town but also 47 out of 63 municipalities around Japan. However, in 16 municipalities people from higher economic backgrounds attended the community-based activities more than those from lower economic backgrounds. Therefore, we need to observe and analyze them closely in order to spread activities which are likely to reduce the gap in participation and to avoid activities which tend to widen it.

Dr. Holman:

I cannot agree more on the last point. When we implement well-meaning interventional policy without attention to inequalities, we can inversely increase the gap, and from a public health perspective, this is absolutely not what we want to do. I think that these activities have strength in that they are happening in the same community because people who live in the community have something in common, so this is a way to create bonds and increase participation.

Dr. Ota:

Lastly, I would like to ask two of you what people can do in daily bases in a personal level or community level to reduce health gap.

Dr. Holman:

This is actually a very challenging question. I agree that this is multi-level problem and multi-disciplinary in an academic perspective. Healthy aging, aging, health inequality, these topics must involve different disciplines and there needs to be more of that. People are still likely to be working solos, and the only way to tackle the problem is to work together in different disciplines. In terms of what people can do in daily lives, they can try to take care of their own lives but they can only do that in the context in which they live. You cannot get away from the importance of social determinants, living and working conditions, green spaces etc. all these things are fundamental.

Prof. Kondo:

This is a very challenging question to answer in a limited time, so please read my book released in June this year. This book tells you things that individuals can do as well as things that should be done in community and national levels.

The symposium came to an end with the closing remarks by Professor Toriya.

Note: The affiliations of the lecturers are as of October 20, 2022

Keio University Global Research Institute (KGRI)

Extending Healthy Life Expectancy Project team

E-mail: kgri_2040pj@info.keio.ac.jp