[Dialogue] Yasue Mitsukura × Masatoshi Kokubo

Considering the relationship between humans and technology from the perspective of "cognitive liberty"

Brain-Machine Interfaces (BMIs) are in the spotlight as a "dream technology," which will allow users to operate devices using only their minds. This is a technological domain with huge potential applications in connecting human brains to machines to support the lifestyles of patients with intractable neurological diseases and spinal cord injuries. Meanwhile, it is important to envision the imminent future and remain level-headed while debating the merits and demerits of these technologies in order to make progress toward their real-world implementation.

In Japan in particular, advanced technologies often seem to lead to a broad sense of trepidation among the general public, and achieving a deepened understanding of the science behind them is currently at an impasse. This is precisely why there is an urgent need for comprehensive discussions about these technologies to take place across disciplines, including medical science, engineering, the social sciences, and philosophy. Interdisciplinary research in neuroscience and law--referred to as neurolaw--has particular potential to map out an improved social model by investigating the balance between the advancement of neuroscience and regulation thereof.

With this sense of crisis as their starting point, Professor Yasue Mitsukura of the Department of System Design Engineering at the Faculty of Science and Technology--whose research deals with BMIs, among other technologies--and Project Researcher Masayoshi Kokubo, of the Graduate School of Law--whose research is on neurolaw and "cognitive liberty" to bridge the divide between humans and machines--sat down for a Dialogue to discuss the issues from their respective perspectives in biomedical engineering and neuro-law.

Yasue Mitsukura

Professor, Department of System Design Engineering, Faculty of Science and Technology, Keio University; Vice Director of the Keio University Global Research Institute (KGRI)

Following graduate studies at Tokushima University and the University of Tokyo, appointments have included Assistant Professor at the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology. Appointed Associate Professor at the Department of System Design Engineering in the Faculty of Science and Technology at Keio University in 2011, with current appointment starting from 2018.

Researches on extracting information from biological signals, voice, and images using signal processing, EEG analysis, AI-based pattern recognition, and impression analysis. Current topics include systems for the real-time communication of thoughts, and stress detection through bioinformation analyses, among other priority areas.

Masatoshi Kokubo

Ph.D. program Project Researcher, Keio University Graduate School of Law

Born in Tokyo in 1995. Entered the Graduate School of Law after completing Master's Program at the Keio University Graduate School of Law and Graduate School of Science and Technology. Professional experience includes RA for the Program for Leading Graduate Schools from 2018; KGRI member from 2019; and Part-time lecturer at the Toho Junior College and College of Music from 2021-2022. Research focuses on neurolaw, an interdisciplinary domain combining neuroscience and law, with an emphasis on "cognitive liberty."

"Neurolaw": An interdisciplinary domain to consider the relationship between technology and humans

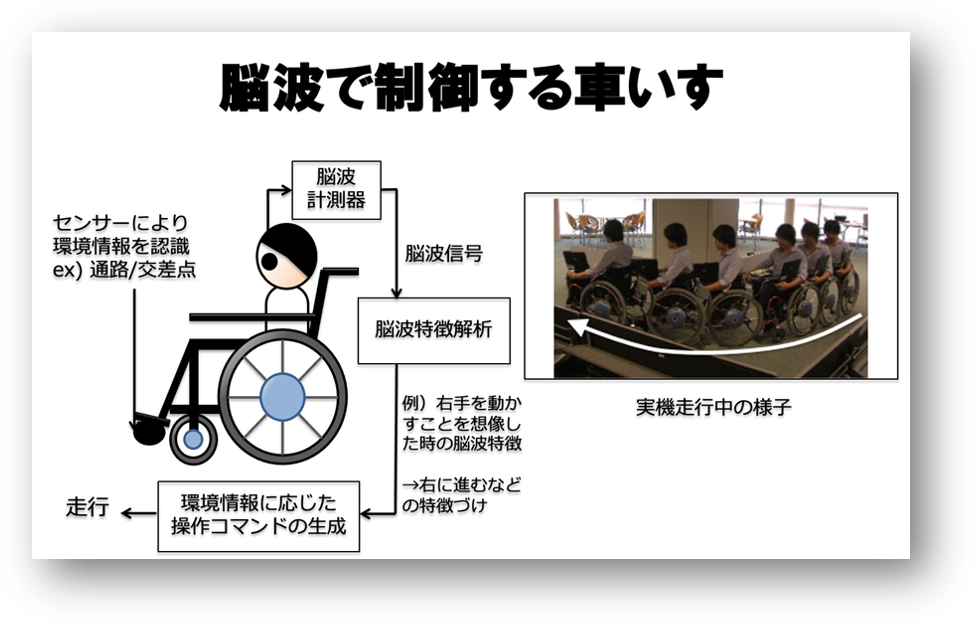

Yasue Mitsukura: My current work is concerned with BMIs, which connect brains to machines, and BCIs (Brain-Computer Interfaces), which connect brains to computers, as well as research on extracting information from biological signals, audio, and images. While these technologies have considerable potential benefits in supporting the future development of society, there are also inherent ethical concerns. Meanwhile, many people are resistant to the idea of connecting a human brain to a machine or computer. To ensure that the technology is deployed safely and effectively into the future we must encourage ethical explorations and legislation. We also need to see that any discussions be based on cross-disciplinary perspectives across fields including law and philosophy, as well as the medical sciences and engineering.

Masatoshi Kokubo: I couldn't agree more. The work in which I myself am engaged in the face of these issues is in the field of neurolaw, which integrates neuroscience and law. The aim of neurolaw is to bring to life a more encompassing picture of what a better society would look like by investigating how protections and regulations should be balanced, while covering the issue of what should be promoted and from which point regulation is needed in the development of technologies. Although a one-dimensional apprehension of the law as to being anything which "leads to regulation" is prevalent, I believe that another role of discussions in the field of law is to encourage technological progress and social implementation by defining the scope of what is acceptable.

Mitsukura: Legislation being behind the game is one of the major challenges in the Japanese sphere, making the start of discussions around this issue essential. The first question that begs asking is "What is the purpose of these technologies?" For example, developing a wheelchair which allows ALS sufferers who cannot get around independently to move using their thoughts alone would be seen in a favorable light by society. Would the same be true however of an able-bodied person going beyond the parameters of receiving treatment for a condition in order to enhance their physical capabilities?

Whereas the status of such discussions is lively overseas, and in the United States in particular, Japan currently lags far behind the rest of the world. That is to say, there is a paucity of opportunities for developmental discussions in a context in which only a vague image of the actual issues prevails. If this situation persists, it will not be conducive to healthy environments, and the research itself will be endangered. This will result in a rapid overseas outflow of outstanding technologies and research talent. This is my sense of the crisis. How did you first encounter this issue?

Kokubo: It may come as a surprise, but my formative experience was watching Hayao Miyazaki's Princess Mononoke, a film I loved as a child. By my parents account, even though I was only 5 years old, I cheekily proclaimed "The future is symbiosis" (laughs).

Even as a child, I found myself admiring the battles of the main character to become a bridge between the worlds of the gods, animals, and humans in the conflicting worlds of the Forest and Iron Town. I believe that this predilection led me on the path to my current life work of research.

Mitsukura: That is certainly a unique motivation (laughs). This means that even as a child, you had begun to be preoccupied with the relationship between human technologies and nature, and the social issues that arise from this relationship.

Kokubo:I couldn't have put it better myself. My horizons were further expanded when I was in junior high school. A biology teacher recommended that I attend a lecture on iPS cells, and I became enthralled to the possibilities of life sciences. This led me to want to explore ways to ensure "The Forest and Iron Town" could live in symbiosis from scientific perspectives. During my high school days I participated as a research student in a project coordinated by Professor Masaru Tomita of the Institute for Advanced Biosciences (IAB) at Keio University, where I worked on oil-producing microalgae.

However, following the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, a climate of distrust in science was stirred up in Japanese society, and I was obliged to invest a lot of thought in how to combat a situation whereby all technologies of an advanced nature were lumped together in a box labelled "scary." Just as I was worrying over how society could be reconciled with science I came across law studies. A constitution is intended to define the freedoms of citizens and to give shape to society. Using a similar perspective could allow us to chart the way towards a grand design of a better future. With this in mind, I went on to study law at the Faculty of Law at Keio University.

BMIs, self-driving cars, and advanced technologies and ethical concerns

Mitsukura: From your own perspective, you have discerned a path that leads to both the worlds of human beings and those of nature, society, and science.

Kokubo:Yes indeed. However, when I met Professor Tomita a number of years ago, and told him about my aspiration of becoming a mediator between the humanities and sciences, he insisted that I should first achieve an exhaustive scientific rigor. After reflecting on the wisdom of this advice, I joined the Program for Leading Graduate Schools, which aims to integrate the humanities and sciences, in 2018. With the benefit of your guidance, I obtained a dual degree of Master of Laws and Master of Science.

Through these processes and my research endeavors, I have myself been exposed to the potential of BMI technologies in freeing humans from various constraints. I have a real feeling that such a reality is now in the imminent future. This is why my own mission today is creating better opportunities for dialogue while maintaining my ties with both of these worlds.

Mitsukura: The issue is that even while the technology makes strides, the public perception of this technology is unchanged. For example, "digital humans," including AI characters and avatars in the virtual realm, are taken for granted among young people, despite their not having minds like humans. So, if we were to embed a human mind in a digital entity, should this entity be considered human? I think it is essential that we increasingly engage the public in such discussions.

Kokubo: What now need to be addressed are the ELSIs (Ethical, Legal and Social Issues). There are those who consider the mind and the brain one and the same, and others who believe they are two completely different things. In the field of philosophy, this is referred to as the mind-brain problem. These and similar issues are extremely deep, and for this reason they must be thoroughly discussed from many perspectives.

Professor Michael Sandel, a political philosopher based at Harvard University, has pointed to the blurring of the boundaries between treatment and enhancement. The prevailing view is that "treatment" is that which is intended to "restore" impaired functions to a particular level, while "enhancement" is that which increases physical or mental functions beyond that level. However, the arbitrary nature of this agreed-upon "level" has been highlighted, and if what this constitutes is essentially the same, the difference between the two becomes even more ambiguous. I think that discussion of this in Japan has been circumvented simply because "the technology has yet to catch up."

Mitsukura: This is exactly the area in which we must intervene. For us as researchers, the issue of legislation is another key concern. As the relationship between humans and machines becomes increasingly entrenched over time, we will surely have to deal with questions about what we actually are, and the limits of what makes us human.

Kokubo: In recent years, the boundary between the "self" and the "other" has been blurred by the expansion of this "self." A case in point is, if a prosthetic hand is to be considered "an extension of the human body," then archiving information beyond that which we are capable of remembering on a computer might be considered "an extension of the human mind." It has also however been noted that cognitive processes can potentially be connected to others or to an AI using BMIs or BCIs. If this should come about, where then are the boundaries of the self to be located? In light of the technological developments and social changes, I believe that we have reached the point in time when we must reassess the very nature of human existence and the "anthropic principle" itself.

Mitsukura: Automated vehicles are a clear example in this regard. To what extent is the driver responsible and to what extent is it attributable to the machine when an accident involving an automated vehicle occurs? The principles by which we decide will change depending on whether we are dealing with semi- or fully-automated systems. The answer is still up for grabs, but many similar problems will emerge going forward, as we expand the human body and mind.

Kokubo: Related to these issues, I am now largely researching on a new concept of liberty referred to as "cognitive liberty." This refers to freedoms in the realm of making plain a person's cognitive processes or making those processes subject to interventions. However, if we are to discuss whether "the mind is implicated" in interventions in cognitive processes, we must first refer to findings and know-how in various disciplines. These include the concept of mind-body dualism and the mind-brain problem in philosophy, and cognitive neuroscience in the scientific realm. That is to say that, in the absence of interdisciplinary research, we will not even begin to get a handle on the most advanced science and technologies.

For example, a person's innermost thoughts can be changed by simple exposure to the words or artistic creations of others. To what extent then is there a difference between such changes and the changes induced by electrical, magnetic, or other stimuli? It is my belief that interdisciplinary research is what is needed to deepen our understanding of such things. Naturally, we are compelled to protect that which must be protected. Nevertheless, if we remain frozen in directionless fear and ignorance, there is the prospect that the potential of these technologies will be wasted, along with the promising futures which they may have heralded.

Cross-disciplinary debate is needed to show the way to a happier society

Mitsukura: For my own research, BMIs and BCIs are technologies set to promote mutual understanding and support the lives of many in the aging society to come. However, even if we offer explanations to the effect that these technologies are intended to improve people's quality of life and contribute to the happiness of all, there will be objections from humanitarian perspectives as soon as we mention placing implants in the head. If these technologies are used on the basis of predetermined rationales they have the potential to alleviate human suffering and make the world a considerably better place. Unfortunately, where we currently stand is that even the avenues for imagining these possibilities are closed off.

Kokubo: There is a strong tendency for people to fear unfamiliar technologies, and this is borne out by any number of historical precedents. These include the "Luddite Movement," whereby workers in England during the Industrial Revolution mobilized for the destruction of machines. That said, when coming to grips with a new technology it is imperative to rationally assess both its potential and inherent challenges. In other words, what is needed is an embracing knowledge which transcends disciplines. We should then envision our ideal futures, and use these as our starting point to work back to our present. Further, I think it is necessary to establish a social consensus on how far it is acceptable to go with these technologies.

Mitsukura: I totally agree. Even though this has now long been a matter of fact, in the past there were those who struggled to believe that a "lump of steel" embodied by an airplane would be able to fly. We must devise the process by which we change the mindsets of those who would be inclined to completely disavow of the notion of exposing brains to external physical stimulation. After all, Japan is the first country in the world set to become a super-aging society. Another way to look at this is as constituting a wonderful opportunity for Japan to be a global forerunner.

Kokubo: The ethical standards in the field of regenerative medicine in Japan are known as the "Japan Model." We would like to devise a similar model in the field of neuroscience. Therein, in fact, lies my own ambition.

Mitsukura:That is a wonderful ambition to have! In this sense there are many things in the world which are still virgin territory, and this is not limited to technology. One of these is the effect of hormonal fluctuations on the body and mind. The perception exists that this is an issue which is the exclusive domain of women, but men too are subject to hormonal cycles, including menopause. Symptoms that had previously been attributed to mere aches and pains are now established as being as a result of the male menopause...although we remain a long way from establishing all the facts.

Kokubo: I had no idea! I think it would be a dream come true if developments in technology allowed us to apprehend the various symptoms and phenomena that were previously overlooked, and facilitate us in leading healthier lives.

Mitsukura:It would, definitely. What I am conceiving of is a sensor in the shape of a ring. For example, would such a device allow us to work and live in step with our unique biorhythms, to ensure that we are properly rested during periods of hormonal imbalance and that our performance is optimal when these balances are at favorable levels? If we went a further step and distributed these sensors to elementary school students, we would go some way to helping them in their future educational path by familiarizing them with their own bodily functions. We are of the belief that a significant percentage of cases will be found where symptoms previously attributed to depression are in fact the result of hormonal fluctuations.

Kokubo: Rather than basing one's approach on the technologies or real-world implementation, what can we do to enhance future society and the quality of life of each individual? I think it is very important to start with this stance. To do so, we will also need to create the mechanisms to objectively understand and discuss what is currently underway. I have a renewed sense that this is the crux of the matter.

Mitsukura: We are steadily ascending through the steps which will bring us to our goal of bridging the divide between humans and nature, and between the humanities and the sciences, as mediators. I would be delighted if you could engage with this role of facilitating dialogue across disciplines. It would be a thing of wonder if the medical sciences, economics and the arts could link up.

Kokubo:Thank you for these comments. Above all, I find my motivation in this urgent sense that "things can't go on as they are." If nothing is done to address this issue, we may be faced with polarization, whereby people either have a misplaced fear of science and technology or unconditionally sings its praises, as typified by utopian and dystopian takes on AI. Achieving an embracing know-how transcending disciplinary barriers will be of the utmost importance when it comes to successfully deploying these technologies as a means to pave the way to the future while avoiding the pitfalls of the polemics engendered by encounters with unknown technologies.

The Cabinet Office's "6th Science, Technology, and Innovation Basic Plan" also makes reference to "encompassing knowledge integrating the natural sciences, with the humanities and social sciences." To put this into practice, we need people who can translate and mediate among the languages of respective fields, and from broad perspectives. It is furthermore important that we envision futures in which the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences will work together, and proceed from this point. I will continue to strive to be a person capable of contributing to the realization of such futures, however modest that contribution may be.

This dialogue took place on November 5, 2021 at Yagami Campus.

*Affiliations and positions listed are those at the time of the event.