【Interview】Professor David Farber (Part 3) - Stories Behind the Computer Science Network - The Blossoming 1980s

2019.03.26"I always consider my career at Bell Labs as somewhat academic," Farber says on his career switch from Bell Labs to the Rand Corporation in the late 60s. "So, this might be the beginning of my industrial career."

The days he spent at Rand Corporation, a not-for-profit think-tank, was, in Farber's words, a "unique experience." He was in a computer science group, and "in hindsight our team was supplying the technical input to the rest of Rand."

He was involved in eight programming language projects, perused the rich selection of materials in the library every morning, and enjoyed the endless lectures and seminars--some classified--which satisfied his intellectual curiosity.

"We did whatever we felt like doing. We also tried the experiment of locating where guns were shooting from during the Watts Riot using computer techniques."

"It allowed me to broaden out, quite a bit.... This is also the place where Paul Baran and I became good friends. We remained so for the rest of our lives." Farber and Baran later published a sensational article together, a pinnacle moment in their careers.

Farber's position in Rand Corporation was followed by one at Scientific Data Systems--later known as Xerox Data Systems.

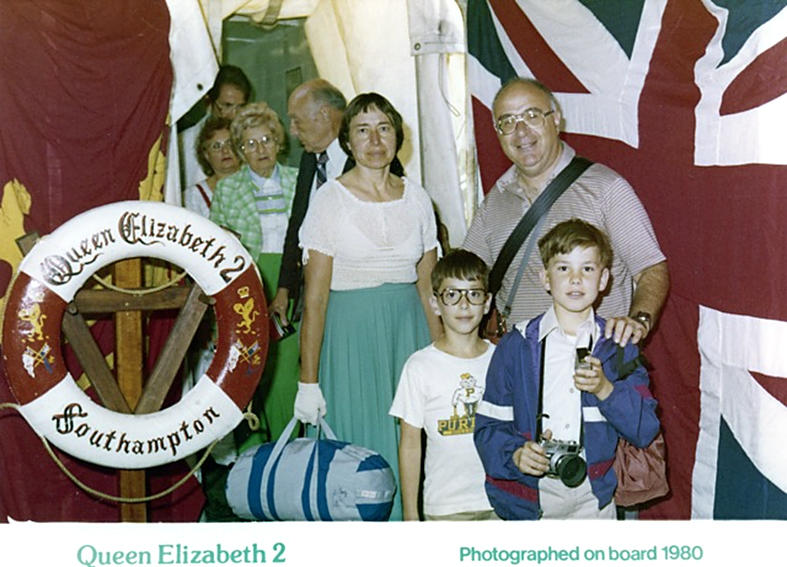

"Back then, I had been teaching a class in the evening at University of California, Irvine ... when I was asked to become an associate professor without tenure. I had just bought a house, the first child was on the way, so normally it would be insane to move. But we did."

There, he and his colleagues proposed the first distributed computing system. The US National Science Foundation (NSF) funded it.

"People said 'this is the idea maybe we will do someday,' but we actually did it--in fact we did everything we had claimed. It had lots of interesting things: operating systems, networking, cloud computing environment, and so on."

"But the most interesting thing it developed was a set of students who later became the 'Fathers of the Internet,' such as Paul Mockapetris and Jon Postel."

"Back then, faculty members of Universities of California could advise [anybody at] any of the campuses. I got a call from Gerry Estrin, who was the chair of the Computer Science Department in UCLA. He asked me to take charge as a thesis professor for students who were interested in networking, as they didn't have any faculty member to advise them."

"For instance, with Jon Postel, once a week, we always met at the local pancake place. I ended up gaining 10 pounds," he laughs.

"Communications is now Digital"

As Farber continued to talk with Paul Baran, they decided to write a paper about the "Convergence of Computing and Communications" and published an article in AAAS Science. The argument they used in the paper was that communications is now digital. At the heart of which is computing technology, and they cannot be separated anymore.

"We articulated the fact that the computing world and the communications world are now converged. It was the first paper which made this argument."

The time had come to move yet again. After the first two years, he got tenure and continued his career at UC Irvine, "living fairly happily around 50 miles from Santa Monica ... until the day I got a visit from the University of Delaware."

He decided to move back East, "and it was a good move," he says. "This happened to coincide very nicely with the next step of my career."

"Around the time I moved to Delaware, I had been talking about networking in general with a friend of mine, Larry Landweber."

"Those days, being connected to ARPANET, we realized that it had changed the way we did research. It was the day when all the universities in the US suddenly had computer science departments, but the researchers were scattered, and you couldn't do research unless you could talk to each other. But if you were on the ARPANET, you could communicate with people."

There was a particularly important moment with Landweber at Philadelphia airport, in 1979. "When we got together at Philadelphia airport, we decided--let's do it right. The idea was to supply every computer science department in the US with the capability of talking to each other at least with e-mails, and hopefully more."

They proposed to the NSF that it fund a computer science network that would be built on whatever networking capabilities they had at that point, including ARPANET, x.25, telephone, e-mail exchanges, whatever needed to be done.

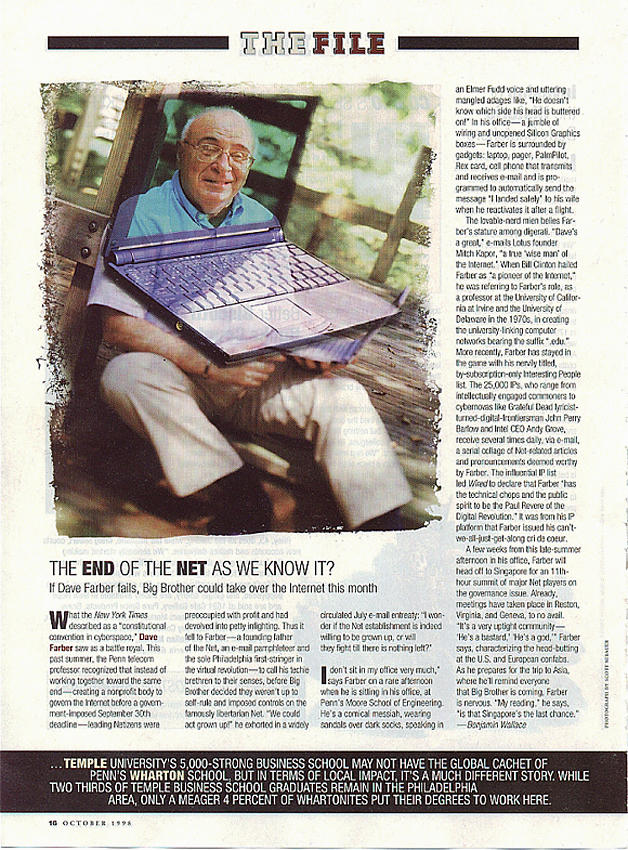

"One could argue that's where the 'Internet' began," says Farber, the "grandfather" and creator of the original form of what now is known as the Internet.

Things moved quickly. In reaction to the proposal by Farber and Landweber, the NSF agreed to fund the network for 3 years. Farber's team got funding with 5 universities collaborating, and they started deploying the computer science network (CSNet). Three years passed.

"We ended up with 450 universities part of it. Universities were asked to pay a modest amount of money, from 2,000 to 10,000 US dollars."

"Then we were asked by the research labs, such as IBM, Xerox, and others, which tried to hire the students from the universities saying, 'can we get them access to CSNet?'"

"We argued and answered, 'if it was supportive of computer science, we were happy to [grant them access].' They joined for 25,000 US dollars a year. They signed up and ended up paying for a large part of it."

That was the moment when CSNet brought together academic science and industrial science, ringing the bell that launched the Internet.

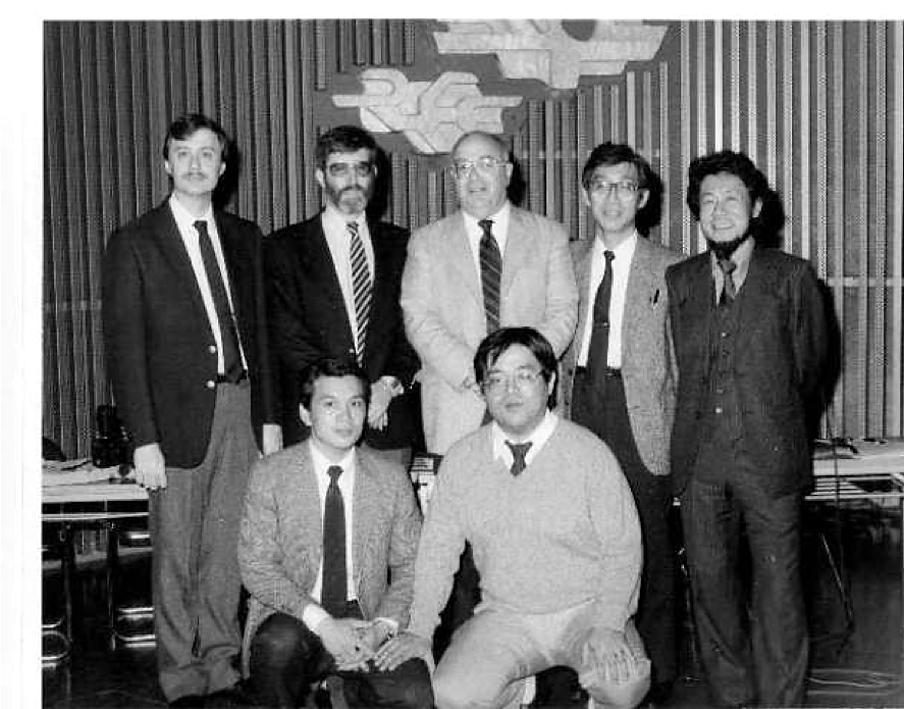

They also started to expand the network to overseas, including Japan.

"Larry and I came to Japan, mag tape in hand--picture of Jun and Hide [Professor Jun Murai and Professor Hideyuki Tokuda of Keio University]. We wanted connections with Japan. I had already met Professor Aiso [Professor Hideo Aiso, also of Keio University]. Aiso gave the tape to Jun and Hide, saying 'make it happen.' It launched and evolved."

CSNet spread rapidly. The success of networking in the computer science area at the universities got other departments of universities--departments of philosophy, physics, etc. to say, "can we use it too?" Farber, as a head of an advisory board for the networking of NSF, proposed that NSF create the network called Sciencenet, but for copyright reasons it became NSFNet.

"We expanded into NSFNet," says Farber. "NSFNet expanded to the national research and education network; NREN. That was done to allow it to go out to profit-making organizations. And at that point we regionalized the network in the US, and we created profit-making regional networks. And off it took."

There was another important thing they started.

"I was wondering why we were not capable of high-speed network. It was partially because the people those days didn't believe they needed speed, and partially because they were not sure how to do it. I proposed we deploy a gigabit testbed."

Farber and Robert 'Bob' Kahn made a team to start deploying the project. Then a big point of contention arose again. "It was a classic argument of 'who needs it?' You don't need it until you have it," Farber muses.

"Five universities and five companies agreed to work together if the NSF could provide some money. I back-channeled the proposal to the director of the NSF who I had known for a long time. He thought it was a good idea and questioned whether we had support from companies. I told him we had already had an agreement from IBM to join in. 'OK you win,' he said. The reviewing process went well, and NSF agreed for the 3 to 4-year funding. Here we started."

After 4 years, they developed the whole set of the first Gigabit Testbed. By this time, Farber left Delaware and moved to the University of Pennsylvania.

"One morning before my first cup of coffee, I got a call from a strange voice, which turned out to be an invitation from the University of Pennsylvania."

They wanted Farber to move to Penn. Farber discussed it with his wife. "Delaware was a comfortable place to live. But in the long run, it was a good opportunity."

They decided to move, and it was in his words, the "right choice." Farber's team completed the gigabit testbed at Penn and had outstanding success, staying at Penn until 2003.

Photo courtesy of David Farber (except for the 1st photo)

(To be continued)