[Event Report] "Democracy in Jeopardy" Brought About by Platformsー Symposium "The Change of Media and Democracy in Digital Society" (December 20, 2021)

2022.06.07

As part of "Platforms and '2040 Problem' Project", one of the pillars of KGRI's "Research Project Keio 2040", we co-hosted a symposium on "The Change of Media and Democracy in Digital Society" with Keio University's Cyber Civilization Research Center (CCRC) and Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST).

Today, political polarization and social divergence are increasing all around the world. Major causes of these phenomena are the emergence of platforms that support SNS and deliver web news, technologies that stimulate users' interests, and the 'attention economy' business model. In a social system where our intentions and actions can be manipulated, how can democracy be sustained? Are there means of survival for democracy?

We invited Professor Lawrence Lessig of Harvard Law School, who was one of the first to raise awareness on this situation shaking the very foundation of democracy, and Dr. Yusuke Narita, an associate professor at Yale University, as guest speakers for this symposium. This report is a digest of the discussions held in the symposium addressing the issue of media environment and the sustainability of democracy.

※Click here to view the video

<Lectures>

Lawrence Lessig Professor of Law at Harvard Law School

Yusuke Narita Assistant Professor at Yale University

<Panel Discussion>

Moderator:

Jiro Kokuryo Professor at Faculty of Policy Management at Keio University & Supervisor of JST-RISTEX "Human-Information Technology Ecosystem" R&D Focus Area

Panelists:

Tatsuya Kurosaka Project Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Media and

Governance at Keio University

Hiroshi Nakagawa Researcher at RIKEN & Representative researcher of JST-RISTEX "Human-Information Technology Ecosystem" R&D Focus Area

Tatsuhiko Yamamoto Professor at Keio University Law School & Deputy Director of KGRI

MC: Haluna Kawashima Project Associate Professor at KGRI

Symposium "The Change of Media and Democracy in Digital Society"

Haluna Kawashima: Hello, I'm Haluna Kawashima, a project associate professor at KGRI. I will be your MC for today. In response to COVID-19 and Japan's entry restrictions, we have decided to change our original plans and hold this symposium online. We thank you for your understanding. Let us commence with greetings from Professor Kohei Itoh, the president of Keio University.

Kohei Itoh: "The Change of Media and Democracy in Digital Society"--- This is exactly the kind of theme that needs to be addressed in the society we live in today. In fact, I was recently contemplating on the roles of the media and the importance of democracy while reading This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends, a book by Nicole Perlroth that won the 2021 Financial Times Book of the Year Award. I look forward to our discussions today.

Tatsuhiko Yamamoto: Hello, everyone. I am Yamamoto, Vice Director of KGRI. I am honored to welcome you to this symposium co-hosted with Keio University's Cyber Civilization Research Center (CCRC) and Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST). Today, we welcome Professor Lawrence Lessig, an internationally respected authority on law, and Dr. Yusuke Narita, who is studying the sustainability of democracy in terms of economics, as our main speakers to discuss about today's speech space, which is becoming ever more controversial with the emergence of filter bubbles and fake news, as well as the structure and environment of 'attention economy.' We hope to shed light on their effect on the media and democracy.

Lecture by Lawrence Lessig "Business Model of a Democratic Culture"

Lawrence Lessig: Today, I would like to talk about the business model of a democratic culture. Let me first show you a video I have prepared for today's online symposium.

There are three claims I'd like to make.

1. Democratic culture has a business model.

2. That business model is a function of that era's technology.

(bModel = f(technology))

3. Cultural understanding is a function of that business model.

(cUnderstanding = f(bModel))

Here, I'd like to introduce you an extreme incident that well depicts this business model. On January 6, 2021, the US Capitol was attacked by Trump supporters who claimed that there has been an election fraud in the 2020 Presidential election. The rioters attacked and occupied the Capitol Complex. The Washington Post reported that more than 70% of Republican supporters believed that there had been an election fraud.

These beliefs are a function of people's understanding (fact = f("understanding")). As aforementioned, understanding is a function of a business model, and business model is a function of technology. The point I'm trying to make is that the understanding of democratic culture is shaped by business model, technology, and their relations to each other.

After the riot, Trump was impeached for allegedly inciting the attack of the US Capitol. Before I go on further, let me introduce you the history of impeachment of US presidents. The first president to be impeached was Andrew Johnson in 1868. The newspaper reports had divided the people to those who were for impeachment and those against it. Though the truth remains unveiled, as there weren't yet any opinion polls back then, I assume the polarization was based on partisanism.

The business model changed greatly as we entered the 20th century. One reason was the start of broadcasting. It became possible for a mass of people to simultaneously access the same information. News report gathered attention from the people as a reliable source of information. Another reason was the birth of "random sampling method" which served as modern means to measure public opinion. We saw how greatly public opinion affected politics in the Watergate Scandal. Since Richard Nixon resigned office before the impeachment verdict was made, an impeachment trial was not conducted. However, approval ratings for the Republicans, Democrats, and other parties all kept dropping as the news unfolded the scandal. This was the result of the people accessing the the same news.

As we approached the 21st century, cable television became available, and the birth of the internet gave way to an explosive increase in the number of media platforms. With more sources of information, most people started losing interest in news and started to polarize again. The fact that approval rate of Donald Trump had hardly changed even after the US Capitol attack indicates that there are multiple realties that people are living in. People only listen to stories that they want to listen to and persist to believe in preconceived notions.

This social upheaval is strongly influenced by the "science of attention." Tristan Harris, former Google engineer and co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology critiques the design method that business model of social media uses to split the public. He asserts that in this method leverages the evolutionary attributes of humans and splits the public by persistently capturing their attention. Surprisingly, this is the same business model underlying the weakening of democracy. As in the case of the US Capital attack, the conservatist network continuously reported that Joe Biden's win was illegitimate, which was then embedded in Facebook's algorithm, spreading hate and vigorous hostile feelings.

We are held accountable for addressing how we want to shape democracy. In the opinion polls conducted by Pew Research Center, approximately two-thirds of American citizens answered that they trusted the public's judgement in 1997 but today, approximately two-thirds answer that they do not trust the public. Can democracy survive in this world where people can't believe in themselves? Please share your thoughts with me.

Lecture by Yusuke Narita "The Curse of Democracy"

Yusuke Narita: Based on Professor Lessig's lecture, I'd like to broaden the discussion in two directions. The first is from the US to the world. Second is from the relation between media and politics to a wider scope of society. I would first like to introduce to you the relation between politics and economics, namely democracy and economic development.

On one hand, universal correlation is seen between democracy indices and economic development in countries around the world as measured by Sweden's think tank, V-Dem (The Varieties of Democracy) Institute. On the other hand, China is drastically growing, even though its index is lower than US and Japan. Furthermore, it has been reported that the economic growth of countries with higher democracy index have been slowing down over the past 20 years. Until the 20th century, democratic countries had a higher GDP growth rate. These rates have become negative as we entered the 21st century.

Let me refer to this reverse phenomenon as the "new divergence of the 21st century." Look at how it developed over time. In the 1990s, we began to see the emergence of the first-generation internet platformers like Google. In 2001, China acceded to World Trade Organization (WTO), which strongly impacted industries in the US and Japan. From 2004 to 2006, second-generation internet platformers, such as YouTube, twitter, Instagram, and Facebook, emerged. After the Arab Spring in 2010-2012, we saw the rise of populist politicians in countries around the world, indicating that social media has begun to have greater effect over politics.

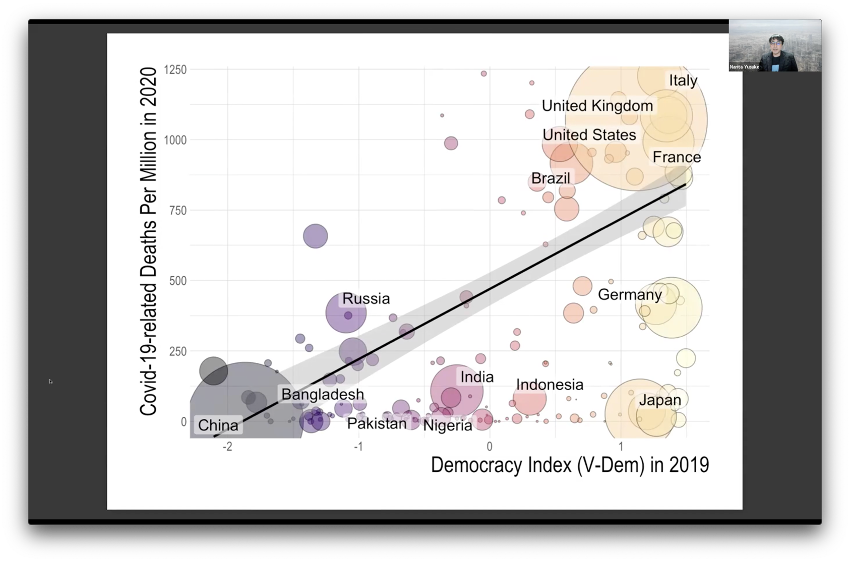

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic swept over the world. This diagram of COVID-19-related deaths per million versus the democracy index shows that there were more deaths in more democratic countries. In other words, over the past 20 years, democracy has put its country in difficult situations, in terms of economy and public health. I refer to this as the "Curse of Democracy in the 21st Century."

What brought about this curse? Professor Lessig has partially answered this question for us. That is, the weakening of democracy. There are several factors that threaten democracy, such as polarization of political ideologies and opinions, hate speeches, and populism. It has become evident that the rate of increase of these factors are greater in countries with higher democracy index. In other words, the more democratic a country is, the more democracy is weakening. We see that democratic countries are struggling in terms of economics, with drops in trade induced by decreasing investments.

The weakening of democracy is not just happening in the US, and it is not just affecting politics and media, but also economics and even people! So, my question to you is, "What should we do?"

Comments from Tatsuya Kurosaka, Hiroshi Nakagawa, and Tatsuhiko Yamamoto

Kawashima: Let us now move on to our discussions. Allow me to introduce you today's moderator, Professor Jiro Kokuryo from the Faculty of Policy Management at Keio University and supervisor of JST-RISTEX "Human-Information Technology Ecosystem" R&D Focus Area.

Jiro Kokuryo: In this section, I'd like to hear from 3 participants. They are Professor Tatsuya Kurosaka (Project Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Media and Governance at Keio University), Dr. Hiroshi Nakagawa (Representative researcher of JST-RISTEX "Human-Information Technology Ecosystem" R&D Focus Area), and Professor Tatsuhiko Yamamoto (Professor at Keio University Law School).

Tatsuya Kurosaka: While working as a professor at Keio University, I am also the CEO of a consulting firm called Kuwadate, Inc., engaging in formulation of management strategies and capital policies for communications and data-related businesses. Through my work, I strongly feel that trust towards traditional media, such as newspapers and television, are being questioned with the diversification of media environment. I also sense the malfunctioning of information distribution and journalism from rising number of ad frauds found on the internet.

We are developing a technology called "Originator Profile" to use third-party verification to reveal information on the originator such as what kind of person is the source of information, his/her organization profile, and their editing policies. We are still unsure whether this will be a solution to current issues the media are facing or if we can develop it fast enough, but many Japanese newspapers have sympathized with us and are supporting our challenge. I would love to hear your thoughts on whether our initiatives will be a solution to the themes addressed today.

Hiroshi Nakagawa: I'd like to hear everyone's opinion on how we could pop filter bubbles, the most representative example seen in Trump supporters, who firmly believe in fake messages distributed on the social media, attacking others for not sharing the same view.

I think one solution is to create an information environment which allows different parties to actively communicate with each other. This may sound like an optimistic idea, but for instance, this environment could be a place where parties talk about topics that do not provoke any political controversies, such as food and sports.

Another solution is to prohibit anonymity on the social media. I understand that some people feel more comfortable speaking their mind because they are anonymous or that using real names can lead to troubles. But couldn't we also say that anonymity has an adverse effect on democracy?

Lastly, I'd like to note that anonymity is closely related to communication privacy. In Japan, the names of the sender and receiver of information are not to be publicly disclosed. However, some take advantages of these rights and send hostile messages. But then again, regulating such communication as seen in Twitter freezing President Trump's account is incompatible with the freedom of expression. How do you think we can find the right balance between the two?

Yamamoto: I'd like to propose 3 possibilities on the themes addressed today from a constitutional law perspective.

First is to think about the necessity to redefine the freedom of expression and speech as measures against "weaponization of emotion" on the social media. I think we need to discuss the fundamental purpose of this right to maintain and promote democracy as the neoliberal interpretation of this freedom, of thinking "it's okay to say anything", is spreading.

Second is to reconsider the theory on freedom of thought practiced in constitutional law. Speech and thought are determined as good or bad depending on the market principle. If attention economy continues to distort market principles, I believe it is necessary for the government to foster a healthier environment.

Third is to think about mind-hacking and how it infringes our "freedom of cognitive processing". By applying cognitive science, users can be manipulated to make certain decisions or be turned into "information addicts" through subconscious stimulations to drive engagement. What can be done in terms of constitutional law to regulate these mind-hacks?

It is also important for us to think about how we can apply technology to slow down or stop the deterioration of democracy. For example, are there any ways to apply a public algorithm that allows users, who have been trapped in filter bubbles by advertisement/commercial algorithms infesting this world, to "open up" to others? In this age where the metaverse is steadily expanding, we need to think about who is the true sovereign of the world, and reconsider the relationship between the sovereign state ruling the real world and the platformers ruling the cyber world.

Discussion: Are there any ways to save democracy from its jeopardy?

Lessig: I loved Professor Kurosaka's idea. I agree that creating infrastructures to verify information is a crucial step to take, though concerns of labeling controversy--one group would contradict another group's assessment on the credibility of the verifying organization--will remain.

I think Dr. Nakagawa has made a valid point on introducing non-political topics as openers for discussions. But we would need to think of ways to prevent politicalizing non-political discussions as we have seen in FOX News politicalizing the issue of mobile phones by emphasizing the dangers of electromagnetic waves and inciting anxiety.

I also agree with Professor Yamamoto's proposal on the need to reconsider the freedom of expression. For example, if the values of speech are to become evaluated by AI, the criteria would not be whether the speech was telling the truth, but whether it has stimulated engagement. This would initiate development of algorithms to manipulate speech. Just like in the way science was used to make people addicted to processed foods, these algorithms may take advantages of our weaknesses. We must think of measures to take to prevent this from happening. Some claim that these algorithms are within scope of the freedom of speech stipulated in the US Constitution, but I strongly think that our democratic society would become extremely vulnerable if our government cannot intervene with these manipulative engines.

Kokuryo: I'd like to hear from our participants on your views on the weakening of democracy as Dr. Narita mentioned in his lecture. How do you think democracy should be sustained? What should REALLY be protected? What defines democracy?

Lessig: The fundamentals that democracy is trying to protect is the division of power. In other words, preventing the centralization of political power. However, over the past 20 years or so, a group of US senators have gained the power to block any laws and regulations. Furthermore, it can be said that Elon Musk, the founder of Tesla Motors, has become so powerful that he has power that surpasses the government and can change the world. I think this is a representative and terrifying example of the weakening of democracy as Dr. Narita pointed out.

Narita: There is a trend among constitutional scholars that seek for governmental intervention in platforms and algorithms. As Professor Lessig pointed out, this is to prevent extreme centralization of power to those few dominant enterprises. So, then the question is, what should we do? I think there are at least three kinds of measures we can take. The first is intervention and regulation of information, communications, and the social media. The second is to redesign the electoral system and processes. The third is to free ourselves from our current form of political systems and nations and creating an independent nation with new political systems. Which measure do you think is most promising?

Lessig: I think we need to simultaneously implement all three. First, prohibit advertising against expressions on politics because capitalist incentives destroy democratic decision-making. Next, we must improve our current democratic system where equal opportunity is not given to all people. Thirdly, we must acknowledge that we are already trying to create a space that is segregated from the concept of nations. We need to determine what kind of system, whether it be democratic or autocratic, is suitable for this virtual world.

The Roles of Journalism, Legal Regulations...Measures we can take today

Kokuryo: Could we wrap up this discussion with a comment from each of you on the roles of journalism in our digital society?

Yamamoto: I think that it is necessary for us to broaden the scope of monitoring, which is the basic role of journalism, to the "power of platform" and "power of algorithm" instead of just monitoring the power of the state. For instance, news indicting Facebook documents that state the services are mentally and physically affecting users negatively sets a notable example on how journalism should act towards practice of such power.

Nakagawa: I think the short cut is to restore democracy in platform giants like GAFA. I think it is prominent to have governments intervene in platform activities in forms such as EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Kurosaka: I'd like to propose two concepts: "Don't trust. Verify" and "Trust. But verify." Oftentimes, we find ourselves in the need to believe in journalism in our lives. I think that when we face that kind of situation, it is critical for us to make sure that we can verify the information provided. I think this will lead to the restoration of a healthy democracy.

Narita: I think the key point of today's discussion was to recognize the need to cool off and slow down engagement and communication in the social media. It can be said that the China and Singapore are already starting to take such initiatives, in a rather terrifying way. How can we concretize and yet differentiate our visions with these autocratic countries? This is a topic I'd like to dig deeper on in the next symposium scheduled to be held in June.

Lessig: I agree that we need to "slow down." We should practice "slow democracy" like fostering slow food culture. We should slow down the speed of gathering information which are being machine-processed, because this processing speed that is way beyond human capabilities is what is causing this conflicting situation.

Kawashima: Thank you everyone for your participation. Lastly, I would like to have Professor David Farber, the Co-Director of Cyber Civilization Research Center (CCRC), give us his closing speech.

David Farber: When the internet first came out, we were excited about being able to communicate with people around the world to better understand each other and dreamed of world without conflicts. Let us recall those hope and walk together to that future we dreamed of. Thank you all for an exciting discussion!

This symposium was held online with simultaneous interpretation on December 20 th , 2021.

*Affiliations and job titles are as of the date the event was held.